Tuesday, July 16, 2024

The Dictionary of Lost Words, by Pip Williams (2022)

Thursday, July 11, 2024

Common Ground, by J. Anthony Lukas (2015)

In short, there's so much going on in this story! It's like every page is an entire history book of its own. I will not possibly finish it this summer, but what a gem of a text to help me think about issues of (1) individual rights, (2) remedying the wrongs and injustice of the past, and (3) finding ways to build stronger, fairer communities.

Saturday, August 7, 2021

Walking The Nile, by Levison Wood (2015)

Levison Wood is a British explorer and travel writer who set out to become the first person to walk the length of the Nile River. His book is engaging and informative. The narrative combines personal emotion, natural description, historical overview and cultural observations. I enjoyed learning about the history and culture of Uganda:

On the forty-seventh day of our journey [Wood travels the first leg of with a gregarious Congolese man named Boston], Kampala came in sight. We were up before dawn, walking through the pitch black, past lay-bys where lorries were emblazoned with banners declaring 'God is Great, God is Good, God is Everywhere!' and along a road where the traffic police kept demanding to know what we were doing ... Kampala is a teenager of a city - boisterous and messy, contradictory but naive and growing fast ... in this city of a more than a million people there are a great number of different cultures existing side by side.

Although the Buganda, the local ethnic group, make up more than half the population, the city's ethnic mix is truly diverse. As in most modern countries, the growth of the urban economy has seen people flock to the capital - but Kampala's expansion has been driven by political factors too. During the rule of Idi Amin, and Milton Obote - who was overthrown by Amin and then restored to power following Amin's deposition - many Ugandans from the native northern tribes were brought into the city, to serve in the police and army and to shore up the government's other, more shadowy security forces.

I've heard of Idi Amin. He resides in my consciousness as an intimidating, scary dictator of my youth (alongside Pol Pot and several others), but I think I placed him in southern Africa instead of properly in the north. I wonder whether he was supported by American and/or European governments, as a misguided attempt at maintaining "security" in a post-colonial world.

----------

Friday, July 30, 2021

Before We Were Yours, by Lisa Wingate (2017)

Before We Were Yours is a fictionalized account of children who were held in the Tennessee Children's Home Society. It is readable and engaging, and alternating chapters are told by an elderly woman who was abducted at 12 (Rill Foss / May Crandall) and a 30 year old politician-in-waiting (Avery Stafford) whose family has kept their ties to the Society a secret.

The Children's Home Society was operated during the first half of the twentieth century by Georgia Tann (1891-19150). She and her staff essentially kidnapped and sold children to upper class families, relying on the argument that they were finding more suitable homes and "helping" all involved.Tann's work was supported and/or endorsed by E.H. "Boss" Crump and other influential Memphis politicians. Crump was the mayor of Memphis from 1910 to 1915, and he effectively controlled the city for a couple of decades thereafter.

Thursday, July 29, 2021

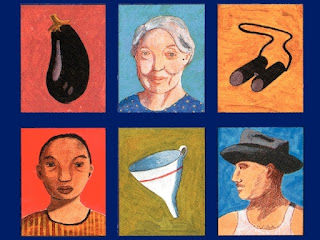

Seedfolks, by Paul Fleischman (1997)

This is a beautiful book. Fleischman's ability to imagine a range of separate but interconnected lives provides a powerful reminder of the way in which we are all part of something bigger than ourselves. He has a unique capacity for empathy which inspires me to become more empathetic.

I like, too, the way in which there is a specific geographic setting -- a neighborhood in Cleveland -- because it demonstrates that places matter in our lives. Places become a part of our identity, and their details and unique characteristics shape us in a variety of ways.

The ongoing metaphor of seeds growing and changing, and the cycle of seasons and lives, seems straightforward, but the way that Fleischman develops the metaphor is poetic and moving.

An excerpt from the chapter "Sam":

Squatting there in the cool of the evening, planting our seeds, a few other people working, a robin signing out strong all the while, it seemed to me that we were in truth in Paradise, a small Garden of Eden.

In the Bible, though, there's a river in Eden. Here, we had none. Not even a spigot anywhere close by. Nothing. People had to lug their own water, in buckets or milk jugs or soda containers. Water is heavy as bricks, trust me.

And new seeds have to be always moist. And in all of June it didn't rain but four days.

Monday, July 19, 2021

Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens (1860)

Charles Dickens creates authentic and engaging characters better than any other author, past or present. The tiniest details about his characters make them come alive. I wonder how Dickens found the time to observe enough people to come up with all of the different characters -- did he carry around a notebook in which to record hundreds of observations, before using them in his stories?When I read Great Expectations in 9th or 10th grade, Miss Havisham made a particular imprint. I imagined her in a dark, dusty, cluttered room, and I wondered whether in Pip’s shoes I’d have been frightened or fascinated.

Here's an excerpt (from Chapter 27) in which Pip learns that Joe is coming to London for a visit, and Dickens incorporates an insightful comment about human nature:

Not with pleasure, though I was bound to him by so many ties; no; with considerable disturbance, some mortification, and a keen sense of incongruity. If I could have kept him away by paying money, I certainly would have paid money

… I had little objection to his being seen by Herbert or his father, for both of whom I had respect, but I had the sharpest sensitiveness as to his being seen by Drummle, who I held in contempt. So throughout life our worst weaknesses and meannesses are usually committed for the sake of the people whom we most despise.Another fascinating character is Mr. Jaggers, the lawyer who oversees the trust for Pip and who walks through his life with self-confidence that does seem characteristic among effective lawyers. Jaggers does not suffer fools, and he does not seem to have a sense of humor, but he’s not without merit: his deep understanding of (and commitment to) the law seems to imply the law is where he finds his own meaning. Oddly, though, Dickens describes the way in which he thoroughly washes himself at the end of each workday, as though scrubbing off the reality of the things he’s done and the people with whom he’s interacted. The washing ritual is particularly poignant at this moment in time, when we’ve all become much more conscious of washing because of the pandemic.

I’m curious to know whether we read an abridged version of Great Expectations in high school. I remember very few of the characters, and the plot seems too dense to have handled at that age. Maybe I’m not giving high school readers enough credit, but my hunch is that we read a version that focused on the interactions with Miss Havisham and left out some of the other details.

Wednesday, June 30, 2021

Learning to Pray, by James Martin, SJ (2021)

Martin writes with impressive clarity. I love the way that he weaves together personal anecdotes, historical context, and theological rumination.

His books make me think about Father Hicks and the other Jesuits at Nativity. They had a significant impact on my life, both in terms of introducing me to the joys of education and providing a model for the contemplative life. Martin writes about the Jesuit Retreat Center in Gloucester, Massachusetts, which I believe is where our faculty spent a couple of days in 1996 or 1997.

-------------

Beginning when I worked at Nativity, I have heard about the Spiritual Exercises, but I have not read the book nor was I familiar with any of the details. Martin's explanation of Ignatian contemplation (beginning on page 238) is fascinating.

The idea is that you picture yourself in the midst of a Biblical story or scene. You use all of your senses to imagine as many details as you can. You establish the scene, and then you let your mind roam freely and see what happens. Here is part of Martin's explanation:

St. Ignatius did not invent this type of Christian prayer. It probably dates from the first person who heard the story of one of Jesus's miracles and imagined what it would have been like to have been there ... More than a thousand years later, St. Francis of Assisi encouraged people to place themselves in the scene when he created the tradition of the Christmas creche...

But it was Ignatius who popularized imaginative prayer in his 16th century manual Spiritual Exercises, where it is the basis of much of the prayer in that book. This was one of Ignatius's favorite ways to help people enter into a relationship with God, and it flowed from his own experience...

As with any prayer, first ask God to be with you and help you. St. Ignatius often suggests asking for a specific intention, for example, to be closer to God, to understand Jesus more, to experience healing. He also asks us to be generous in our prayer, not only with our time, but with how much of ourselves we give. By "giving ourselves," I mean being as present, aware and attentive as possible, remaining open to wherever God might lead us; and being willing to spend whatever time we allotted for our prayer, even if it seems dry.

Earlier in the book, I enjoyed reading Martin's explanation of the power of rote prayers (page 118).

I have been saying the Lord's Prayer more than "original" prayers in the past couple of months, so this portion of the text feels very relevant.

Martin states that we pray rote prayers for a number of reasons:

First, we know them. In times of struggle or when words fail us, it's helpful to have a "premade" prayer. Having them memorized is of even greater help...

Second, they have distinguished history. Many rote prayers come from significant religious figures. The most obvious example is the Our Father, which came from the lips of Jesus himself after the disciples said to him, "Teach us to pray." That alone should recommend the Our Father.

Third, when we pray them, we united ourselves with believers throughout the world and down through time. Have you ever wondered how many people are praying the Our Father at the same time you are? The prayer connects you to believers around the world in a way that is mysterious (you can't see them) but real (you know that people are surely praying the prayer). Thus, when you pray the Our Father, you are engaging in a communal act of worship.

Finally, I find Martin's steps for reading sacred texts to be helpful (page 266). He says this process is called Lectio:

1. Reading - What does the text say?

2. Meditation - What does the text say to me?

3. Prayer - What do I want to say to God on the basis of this text?

4. Action - What difference can this text make in how I act? What possibilities does it open up? What challenges does it pose?

Friday, June 18, 2021

Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon (1977)

A point of particular genius is the way that she writes dialogue.

It's fun to read this book just after Shakespeare, who is also a master of dialogue. Shakespeare's conversations, though, have a very different shape and texture. His characters speak to each other in a way that is theatrical and hard to imagine actually transpiring.

Morrison's characters engage in conversations that feel authentic. I love the small details, the non sequiturs, the putdowns, the riffs, and the tender moments of compassion and forgiveness.

Morrison's dialogues have the effect of helping me realize that our relationships -- and in a broader sense our lives -- are a compilation of conversations. Taken individually, a single conversation might not feel significant or earth shattering, but woven together they become our connections, our memories, our emotions. I cannot think of another author with quite the same gift for conveying the way that people communicate with one another.

-----

I had forgotten the way that Song of Solomon is, on one level, a treasure hunt (in this sense, there's a connection to The Count of Monte Cristo).

The way in which Macon Dead Jr., Milkman, and Guitar seek the stash of gold (does it truly exist?) raises all sorts of questions about capitalism and, more generally, the things we choose to search for. Yet the layers of family history (revealed through a series of carefully parceled and extremely engaging stories) communicates that our relationships are truly the core of our identity: individual, familial, and societal.

I do love this book. A genuine masterpiece.

Thursday, July 23, 2020

Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, by Diarmaid MacCulloch (2011)

This summer, I am trying to improve my understanding of (1) the history of Christianity and (2) the varieties of belief within Christianity. To that end, I am currently reading (and listening to) Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years by Diarmaid MacCulloch.

There was considerable theological ferment during the 300s and 400s, as Christians debated whether and how to systematize their beliefs. A series of councils developed creedal statements that organized Christian beliefs and resolved (or aimed to resolve) budding controversies.

For example, the Council of Nicaea (called by Emperor Constantine in 325) examined the question of Jesus's relationship to God the Father. The context was that two important leaders disagreed about the theology: Athanasius stated that Jesus had been "begotten" by the Father from his own being (and therefore had no beginning), while Arius believed that Jesus had been created and did have a beginning.

The bishops who gathered at Nicaea overwhelmingly sided with Athanasius; therefore, the Nicene Creed states:

- Nestorius, the bishop of Constantinople (and a follower of Theodore), argued that Jesus definitely had two natures. He attacked references to Mary as Theotokos ("Bearer of God"), because he did not believe it was possible for God to be born; thus, Jesus's human nature must have been distinct from his God nature.

- Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria, Cyril argued that Jesus had one nature that unified his God hypostasis (this word means "person") and his human hypostasis. The idea of one nature is called the hypostatic union.

This is where it gets extremely tricky for me. The Council of Chalcedon tried to thread the theological/linguistic needle between these two positions, and it did indeed satisfy most Christians. Here are excerpts from MacCulloch:

The Chalcedonian agreement centred on a formula of compromise. Although it talked of the Union of Two Natures, and took care to give explicit mention to Theotokos [in this sense, the agreement favored Cyril], it largely followed Nestorius's viewpoint about 'two natures', 'the distinction of natures being in no way abolished because of the union.'

... In the manner of many politically inspired middle-of-the-road settlements, the Chalcedonian Definition left bitter discontents on either side in the Eastern Churches.

On the one hand were those who adhered to a more robust affirmation of two natures in Christ and who felt that Nestorius had been treated with outrageous injustice.

On the other side, history has given those who treasure the memory of Cyril a label which they still resent, Monophysites ("a single nature"), though this label has been widely replaced by Miaphysite ("one nature").

One interesting detail is that the Coptic Orthodox Church has a pope; other than Roman Catholics, they are the only other group to use this title. In the case of Coptic Orthodoxy, the current pope is Tawadros II, born in Egypt in 1952.

Monday, July 20, 2020

The Scarlet Letter (1850)

As I've been reading and listening to The Scarlet Letter these past few weeks, I've decided that Nathaniel Hawthorne's depiction of Pearl (the daughter of Hester Prynne and Arthur Dimmesdale) is quite remarkable. Pearl is truly childlike: unaware of society's rules (and hypocrisies) at some times, then fully aware just moments later.

She has a fantastic ability to entertain herself. The scenes during which she plays joyfully are hitting home for me as I watch J, T and B find countless new ways to amuse themselves during these long days of coronavirus.

Hawthorne had a knack for communicating the thought process (and the soul) of a child that escapes many authors. In truth, Pearl is -- in many respects -- the most interesting and fully realized character in the book. Dimmesdale is so wooden and incapable of empathy as to seem misdrawn (how could his sermons have been so powerful, if he couldn't understand the world from another's eyes?), and Chillingworth is villainous to almost comical effect.

Here's a sampling of Pearl's adventures:

And she was gentler here [in the woods] than in the grassy-margined streets of the settlement, or in her mother’s cottage. The flowers appeared to know it; and one and another whispered, as she passed, “Adorn thyself with me, thou beautiful child, adorn thyself with me!”—and, to please them, Pearl gathered the violets, and anemones, and columbines, and some twigs of the freshest green, which the old trees held down before her eyes. With these she decorated her hair, and her young waist, and became a nymph-child, or an infant dryad, or whatever else was in closest sympathy with the antique wood. In such guise had Pearl adorned herself, when she heard her mother’s voice, and came slowly back.

Friday, July 3, 2020

Macbeth (Part 2)

In a lecture on The Great Courses, Clare Kinney explores the topic of gender in Macbeth.

She points out that Lady Macbeth is the first (only?) of Shakespeare's female tragic characters to soliloquize (in contrast, for instance, to Ophelia). Here's an excerpt from her famous second soliloquy:

In Macbeth, the central word under negotiation is "man."

Macbeth defines being a man in terms of our shared humanity; a "man" agrees to be guided by certain principles and to act in accordance with a shared set of morals. When he (momentarily) decides not to murder Duncan, he says:

Lady Macbeth, on the other hand, argues that a man is one who puts aside all emotion and simply acts -- in this sense, "man" is in contrast to "woman." Here's a portion of her response:

Kinney points out that, later in the play, Macduff proposes an alternative vision of manhood when he tells Malcolm that a true man will deeply mourn the death of his wife and children. After Malcolm urges him to "dispute it like a man," Macduff responds:

634. What are the major feminist critiques of Shakespeare, and how are those critiques answered? Lady Macbeth seems like a problematic character on multiple levels (manipulative, power-hungry, etc.). Is there an argument that she actually empowers women? How does the argument work?

635. Ghosts in Hamlet, witches (and ghosts) in Macbeth. Shakespeare was clearly fascinated with the supernatural and with the ways that our beliefs (and our feelings) can haunt us. Was Shakespeare (or the person who penned the plays under his name) religious? If so, what were his specific beliefs about the afterlife and the role (or not) of God in everyday life?

Sunday, June 28, 2020

Macbeth (Part 1)

I am in the process of reading Macbeth. This play is dark (perhaps darker even than Hamlet).

Shakespeare had a knack for exploring the awful depths to which people are capable of sinking. Macbeth murders the innocent, seemingly with little foresight (this is a major contrast to Hamlet, who broods at length before taking each step).

He is driven by ambition, in particular the desire to rule Scotland. He is willing to kill Duncan (the reigning king), then Banquo, Fleance and Macduff's family (potential threats) in order to keep and maintain power.

631. In addition to President Trump, who are the most nakedly ambitious current politicians and leaders?

632. The numerous authoritarians and dictators are clearly ambitious, and are clearly so in a negative rather than a positive way (I am thinking of Putin, Xi, Erdogan, Bolsonaro). Is there more rampant ambition now than there was, for example, in the 1980s and 1990s? Or is there simply more opportunity to turn ambition towards negative ends?

633. Why was Shakespeare so interested in ambition? I gather that he read tons of history, but how much did he know about the current political affairs of England, Scotland, etc.? Did he view a play like Macbeth as cautionary (in other words, did he want people to read it and think about ways that they could corral ambition?), or was he simply interested in exploring the psychology of leadership?

Here's a sampling of Macbeth thinking about his ambition, in Act 1, Scene 3:

Friday, June 19, 2020

Curtis Sittenfeld's "Rodham" (2020)

I received Rodham for my birthday. This book is vintage Curtis Sittenfeld: fun to read, it raises questions that are provocative but not too deep or serious.

The premise is straightforward. Hillary Rodham meets Bill Clinton while they are both at Yale Law School, but he cheats on her (while Hillary is interning at a law firm in San Francisco) and she decides not to marry him.

After a stint as a professor at Northwestern, she becomes a Senator in 1992 -- defeating Carol Mosley Braun in the Democratic primary, which earns her the enmity of her until-then mentor, an African American woman modeled on Marian Wright Edelman.

I like the way that Sittenfeld imagines Hillary's psychology. She is ambitious but altruistic; practical without completely sacrificing her ideals. She's definitely not perfect, but she's considerably more likable than my-conception of "the real Hillary." Here's an excerpt:

"I had thought that I'd like being a senator; in fact, I loved it. The first speech I ever gave on the Senate floor was about fair housing, and the first bill I ever co-sponsored was the Improving America's Schools Act of 1993, and I loved being able to tangibly and directly take on the problems I had spent my adult life thinking about ... My sense of purpose as a senator made me recognize retroactively that there had been a certain slackness in my life before, or perhaps it was that previously I had been imposing structure on my days and now an external structure was imposed on them. I felt busy in a good way."In a twist, Bill -- having become a tech billionaire after dropping out of the 1992 Presidential race when he and his wife mishandled allegations of infidelity -- challenges Hillary for the 2016 nomination. Bill is not likable at all. Sittenfeld's explororation of Bill's character flaws is causing me to feel even sadder/more frustrated about his personal and political shortcomings.

Saturday, August 3, 2019

The Count of Monte Cristo (1844)

My (limited) knowledge of this book came primarily from The Shawshank Redemption, in which Andy Dufresne recommends Monte Cristo to a fellow inmate because it describes an escape from prison. As I read the book, I enjoyed the way that certain plot details reminded me of Shawshank; it became clear that Stephen King referenced Dumas's classic for more than the surface level reference and follow-up joke.

Fortunately, I found an abridged version at Barnes & Noble (approximately 600 pages). I'm not a fast reader, so even finishing the short version feels like a major accomplishment.

Friday, July 12, 2019

Oedipus Rex: The Question of Fate

Reading the text, I was initially struck by its brevity: less than 100 pages (many of which are quite short because of the back and forth dialogue).

Also, the action begins almost at its climax, as Oedipus asks the people of Thebes to help him solve the mystery of who killed Laius. In truth, I was quite confused with the dearth of background or context, wondering if I had skipped an earlier scene in which the characters and backstory are introduced.

In some ways, the brevity (and climactic-beginning structure) of Oedipus make it very different from Hamlet, in which Shakespeare (and his protagonist!) takes his time at every step of the story. I think part of the reason that I was so surprised with Oedipus is that I assume these famous works of canonical literature must be dense with details and development -- like the Shakespearean tragedies.

In some ways, the brevity (and climactic-beginning structure) of Oedipus make it very different from Hamlet, in which Shakespeare (and his protagonist!) takes his time at every step of the story. I think part of the reason that I was so surprised with Oedipus is that I assume these famous works of canonical literature must be dense with details and development -- like the Shakespearean tragedies.A major theme of Oedipus is the role of destiny in our lives, and it's a fascinating theme at that. Tiresias (a prophet of Apollo) argues to Oedipus that humans cannot escape their destiny, and it's unclear to me whether Sophocles agrees or not. I guess this gets to the crux of the play and its lasting importance: can we shape our own destiny, or are certain things playing out at a level one step removed?

631. It's scary to think that our fate is pre-written, and that if we try to anticipate and change our fate we can actually bring tragedy into our lives. I'm unclear what the ancient Greeks believed about fate: if they were fatalists, how did they manage to create such a dynamic, important culture? I'm also curious to learn more about the attitudes and beliefs, within Christianity and the other major religions, about fate and destiny.

632. What are the various ways in which subsequent authors reference and build-on the themes and ideas from Oedipus? How has it become such a foundational text in Western cultures?

Friday, July 5, 2019

Sonia Sotomayor's "My Beloved World" (2013)

When traveling to New York City last week, I wanted to read a book with a New York setting. I chose Sonia Sotomayor's memoir, My Beloved World.

I have enjoyed this book because it is sprinkled with advice about living a meaningful life, with a major focus on two elements: relationships and education.

Sotomayor's writing style is straightforward, and her passion for living comes across vividly. She frequently writes about how much she enjoys talking to people. I imagine (and am happy to think) that she has forged close relationships with the other Supreme Court justices -- even those with whom she disagrees.

The world that I was born into was a tiny microcosm of Hispanic New York City. A tight few blocks in the South Bronx bounded the lives of my extended family: my grandmother, matriarch of the tribe, and her second husband, Gallego, daughters and sons. My playmates were my cousins. We spoke Spanish at home, and many in my family spoke virtually no English.

My parents had both come to New York from Puerto Rico in 1944 [Sotomayor was born in 1954], my mother in the Women's Army Corps, my father with his family in search of work as part of a huge migration from the island, driven by economic hardship.Her father, who struggled with alcoholism, died when Sotomayor was only nine years old. While she struggled to come to grips with his passing, she turned to books as a source of strength.

She writes a lot about her experiences in school (she eventually attended Princeton), and I particularly enjoyed a passage about being open to learning from each and every person that enters your life:

It was then, in Mrs. Reilly's class, under the allure of those gold stars, that I did something very unusual for a child, though it seemed like common sense to me at the time. I decided to approach one of the smartest girls in the class and ask her how to study. Donna Renella looked surprised, maybe even flattered. In any case, she generously divulged her technique: how, while she was reading, she underlined important facts and took notes to condense information into smaller bits that were easier to remember; how, the night before a test, she would reread the relevant chapter. Obvious things once you've learned them, but at the time deriving them on my own would have been like trying to invent the wheel

... The critical lesson I learned is still one too many kids never figure out: don't be shy about making a teacher of any willing party who knows what he or she is doing. In retrospect, I can see how important that pattern would become for me: how readily I've sought out mentors, asking guidance from professors or colleagues, and in every friendship soaking up eagerly whatever that friend could teach me.

Monday, June 24, 2019

Henry James's "The Turn of the Screw" (1898)

I'm riding the train to New York City, and I've just finished reading (and listening to) The Turn of the Screw.

Of the three classics I've read this summer, this was the densest and most challenging. Henry James writes extremely long sentences. Clauses are embedded within clauses, and it's a real process to suss out the verbs and follow the train of thought. One essay aptly describes James's writing style as Rococo.

The narrator is "the governess", who is hired to care for two children (Miles, age 10 and Flora, age 8) by their guardian uncle. The story takes place at a country manor called Bly, where the previous governess (Miss Jessel) and valet (Peter Quint) engaged in some kind of illicit or inappropriate activity (what they did is not specifically described).

Quint and Miss Jessel both died before the governess's arrival, but they appear as ghosts and continue to interact with the children.

My hunch is that James intended his readers to interpret the ghosts as the psychological invention/imagining of the governess. However, I will need to learn more about him in order to understand what he believed about the supernatural and whether he may have believed in the reality of ghosts.

However, it is an interesting plot point to have Miles's death come at the hands of the governess (as she tries to protect him from Quint's ghost). Perhaps James is aiming to tell us that our fear of ghosts (rather than ghosts themselves) is the true problem.

A final ghost connection: I recently started to read Sonia Sotomayor's autobiography, My Beloved World. Sotomayor describes parties at her grandmother's house during which, after the children have gone to sleep, the adults partake in a ritual in which they communicate with spirits of the deceased (Sotomayor is curious and tries to watch and listen from a neighboring room).

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Pride and Prejudice // The Edge of Anarchy

In my effort to read canonical literature this summer, I'm reading Pride and Prejudice.

To mix things up, I'm also reading The Edge of Anarchy (by Jack Kelly), the nonfiction account of a railway workers' strike in 1894.

The stories told in these two books provide fascinating contrasts.

Pride and Prejudice is the story of Eliza Bennet and her family. It was written in 1813. To demonstrate my lack of knowledge about Jane Austen, I'd always thought that she wrote her novels in the 1870's and 1880's. In truth, she lived and wrote much earlier in the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution was just barely getting started.

Pride and Prejudice is the story of Eliza Bennet and her family. It was written in 1813. To demonstrate my lack of knowledge about Jane Austen, I'd always thought that she wrote her novels in the 1870's and 1880's. In truth, she lived and wrote much earlier in the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution was just barely getting started.It's a story about the five sisters' efforts to find a suitable spouse, interwoven with all sorts of analysis of class and family relationships. There is a considerable amount of humor in Austen's writing, with characters like the pompous blowhard William Collins and the fretting, vacuous Mrs. Bennet. It also contains one of the most thorough accounts of falling in love that I've ever read: whereas most movies (and lots of novels, too) skim over the conversations that cause people to fall in love, Jane Austen devotes many pages to the evolving relationship between Eliza and Mr. Darcy.

I like the organizing framework of The Edge of Anarchy: in order to describe and explain the labor unrest of the 1880's, Jack Kelly first presents short biographies of Eugene Debs and George Pullman.

I like the organizing framework of The Edge of Anarchy: in order to describe and explain the labor unrest of the 1880's, Jack Kelly first presents short biographies of Eugene Debs and George Pullman.I learned about Debs in my 11th grade US History class (Mr. Martin emphasized his five Presidential candidacies, via the Socialist Party of America), but I have not thought or read much about him in the years since.

Born in 1855, Debs worked for railroad companies while young, scrubbing grease from the engines, cleaning the other cars, and serving as a locomotive fireman.

After first becoming involved with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, Debs decided that the various railroad workers' unions were too segregated from each other, which prevented any single union from becoming truly powerful. His solution was to organize the American Railway Union, which welcomed all different kinds of railroad workers -- those with specialized skills and those whose work was considered menial.

For me, one of the key takeaways of Pride and Prejudice is that relationships take time and effort. At a time when digital technology is overwhelming and distracting us, when life's list of tasks sometimes makes the days speed past, this book is a reminder to appreciate the slowly evolving conversation, the (seemingly) mundane details of our surroundings, and the necessity of appreciating every person (including the proud and prejudicial) for his or her own uniqueness.

Wednesday, June 5, 2019

Hamlet (Part 2)

All things considered, however, they are less present in literature than you'd expect. I'd posit that plenty of people are at least open to the possibility of ghosts and spirits ("ghost agnostics"?), so you'd think that famous authors might incorporate them into stories more often.

- Catholics believed that ghosts visited from Purgatory. They were the actual spirits of the once-living humans they claimed to be, and they made requests of the living that would help speed them along to Heaven.

- Protestants believed that ghosts were demons. They were not who they claimed to be; rather, they were agents of evil attempting to corrupt the living.

- Skeptics believed that ghosts were hallucinations.

Sunday, May 26, 2019

Hamlet (Part 1)

One of my goals for this summer is to read some canonical literature.

Inspired by our field trip to the American Shakespeare Company this spring (we saw a rousing performance of The Comedy of Errors), I am beginning the project with Hamlet.

Having read the first two acts, I've learned that he has recently lost his father, and his mother (Gertrude) has quickly gotten remarried (and transferred her allegiance) to his uncle.

The play doesn't explain the ways in which Hamlet was close to his dad, but they must have had a deep and genuine connection. He is confused and troubled by his mother's lack of sorrow -- so much so that he contemplates suicide in one of the early scenes:

This soliloquy was particularly powerful because of the metaphor of the unweeded garden.

April/May/June is the time of year when the weeds are most aggressive, requiring a ton of attention lest they completely conquer the other plants. In truth, I sometimes get frustrated because I want to be planting things, but I feel like most of my time and energy is focused on weeding.

I do, however, like the idea of weeding as a metaphor. Hamlet's speech is a reminder that each of us is constantly tending the weeds in our soul, striving to keep things fresh and positive. Keeping the weeds away preserves the space for growth.